All the Lives We Ever Loved

Image credits: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/55591376645997060/

Preface

My hope with this story is to creatively illustrate some fragments I have extracted from reading Virginia Woolf’s novels, essays, and diaries, and place them in conversation with an author, poet, and female voice that was not only influenced by Woolf, but has greatly influenced me personally: Sylvia Plath.

I am currently conducting research on Plath–someone whose work (and life) shares many similarities with Woolf’s. Through my reading and extensive note-taking on Plath (as with Woolf), I have noticed Woolf’s presence all throughout the former’s work, specifically in her journals. I wanted, through this project, to challenge myself to think outside of my typical intellectual and creative paradigms. I feel that a short story is a great way to put two authors and their individual works in conversation. My overall goal was to create a kind of literary tapestry that interweaves various fragments from the lives and works of Woolf and Plath–something I hope to continue studying in my personal research.

Given that Woolf so often emphasized the importance of the “common mind” and the collective efforts of humanity, I think merging two authors that have had a significant impact on me and my work adheres to that same sentiment. In The Waves, Woolf writes from the character Bernard, “What I call ‘my life,’ it is not one life that I look back upon; I am not one person; I am many people.” I hope this story comes close to adequately epitomizing the collectivity of this project.

All the Lives We Ever Loved

The year is unimportant, the day irrelevant. The exact position of the second hand and the minute hand and the hour hand of the bedside clock is unknown, for there are no clocks in this home.

This is the kind of evening when one seems to be abroad: the window is open; the yellows & greys of the house seem exposed to the summer.

What I can tell you begins with the presence of two women, ageless, in a room of their own. They sit across from each other in front of a tall bay window, smudged with the fingerprints of seasons: the mud, the mist, the dawn. Its center glass pane is wide open, inviting a gentle, sun-filled breeze that brushes against the green walls, flutters the pages of novels along a tall bookshelf, and makes the floral curtains sway as to bachata.

“The first time I entered a psychiatrist’s office, I remember wondering why the room felt so safe.” This comes from the woman seated on the right. Her voice is round and full, spilling like a frothy white wave over the other woman, Virginia’s, body. She thinks the rawness in it is traced by something other than the shape and size of Sylvia’s vocal cords.

“Then I realized it was because there were no windows,” Sylvia says. Her tone indicates a mixture of sarcasm and seriousness.

“Ah, yes,” Virginia says as she returns her smile. “But is a window not better than some old ugly-patterned yellow wallpaper?”

“I should think so,” Sylvia admits. “Especially in that room. The walls were beige, and the carpets were beige, and the upholstered chairs and sofas were beige. And beige, I must say, is much worse than yellow.”

“I would have to agree. And there is something indescribably beautiful about windows. The way they bring in light, each day in a different configuration: miraculously. Frailly. In thin stripes. Hanging like a glass cage…a hoop to be fractured by a tiny jar. There is a spark there. Next moment a flush of dun. I think a nice, big window like this one lessens the barrier between the internal and external worlds–whether one looks out from their bedroom, or gazes up from the lawn.”

“Yes, that is very true,” Sylvia replies. “I have always felt that gaping out my window somehow alters my sense of space. There is, of course, a physical boundary between us and the outside world, but, as you say, that boundary is diminished–in part, I think, by its transparency.”

“Space, yes,” Virginia agrees. “And also time. With my cheek leant upon the window pane I like to fancy that I am pressing as closely as can be upon the massy wall of time, which is forever lifting and pulling and letting fresh spaces of life in upon us. In these moments I find myself overwhelmed by a voice of desire crying, may it be mine to taste the moment before it has spread itself over the rest of the world!”

Sylvia smiles in understanding. “Many days have I spent gazing out my bedroom window pondering just the same thing. Hell, I still do this! I feel I live every moment with terrible intensity. Staring out into the sky’s stagnant blue I whisper to myself,” (her voice lowers and softens), “Remember, remember, this is now, and now, and now. Live it, feel it, cling to it.” Her tone suggests she is still, at this moment, trying to incentivize herself.

“Yes, because even in the faceless blue of the sky,” Virginia adds, “we glimpse the very essence of Life! Floating solemnly in the air, like invisible wisps of hay, of hair, of clouds. And I want to see and feel every single one of them.”

“I want to become acutely aware of all I’ve taken for granted,” Sylvia continues. “All those fleeting fragments–that essence of living, of simply being alive, of sensing the iambic heart in one’s chest, singing, ‘I am, I am, I am.’ That is the voice for me.”

Virginia nods. “This is the secret of happiness, I feel.” She pauses before adding, “But I don’t think of the future, or the past, I feast on the moment.”

“Oh yes,” Sylvia chimes, “I agree. With me, the present is forever and forever is always shifting, flowing, melting. This second is life. And when it is gone it is dead.”

“In a world which contains the present moment,” Virginia adds, “why discriminate? Nothing should be named lest by doing so we change it. Let it exist–whatever it is–this beauty,” (she gestures out the window, then toward her friend), “and I, for one instant, steeped in pleasure.”

Sensing the amplitude of each other’s presence, they are warmed by an air of mutual understanding. “Speaking of being steeped in pleasure,” Sylvia signals with her open hand to the tea table in the corner of the room, “would you like any?”

“Oh, that would be lovely, thank you, Syl.”

Sylvia makes her way to the tea tray. As she gets up, she glances out the window and catches sight of the lustrous garden below. She is reminded of the many summer days she spent setting strawberry runners in the sun. Her lips mold into a soft, effortless smile and she sighs a nostalgic breath.

“Oh, Jinny,” Sylvia adds, looking down at the tray. “I forgot we also have fresh orange juice and steaming café au lait, if you’d prefer that instead?”

Virginia flaps her hand lightly in refusal. “Tea is just fine for me.”

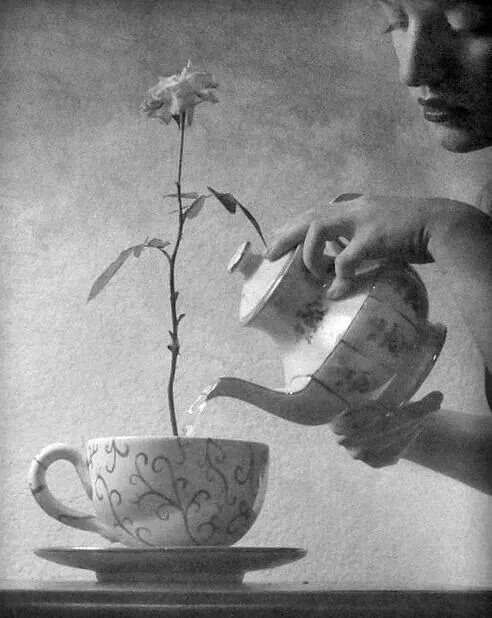

Sylvia lifts the silver teapot with her right hand and pours the steaming, aromatic liquid into two white teacups with blue detailing. Though they appear to be the same cup, they are in fact not: one holds the small outline of what looks to be a cat, though the absence of a tail makes her second guess. The creature’s legs are painted along the bottom of the brittle china, giving the impression that it is headed somewhere. The other teacup is marked by the small but sturdy shape of a horse: riderless, a free thing, God’s lioness. The memory of her horse-riding days gallops into Sylvia’s awareness. She feels, for a moment, that she is back in Devon: between her thighs a bare brown back, the gentle, motherly stroke of her hand along The brown arc of the neck. She, Lady Godiva. An all-consuming yearning to return there creeps into her being.

Sylvia hands Virginia her tea. As the latter lifts the cup to her thin lips, she too takes notice of the blue cat that lengthens its limbs across china. “A queer animal, quaint rather than beautiful,” she notes.

Sylvia retreats to the tea table once again and wheels it over to the windowsill. Virginia sets her cup down, not without first letting its heat spread to her hands. The light breeze has, for some unknown reason, initiated an outburst of shivers across her skin. Sylvia notices this and asks, “Would you like me to shut the window?”

“No, that’s alright,” Virginia replies. “Thank you, though. It seems the older I get the more sensitive I become to the wind.” The breath of the wind is like a tiger panting, she imagines.

Sylvia sits down again. “Now, where were we?”

“The present moment, I believe.” The women laugh. “Ah, but how to focus on the present with the insatiable desire to write something before I die, this ravaging sense of the shortness & feverishness of life, making me cling, like a man on a rock, to my one anchor?” Virginia is exasperated but equanimous.

“And what is that anchor?”

“Writing, I suppose.” Sylvia nods in understanding.

Then Virginia turns the question over to her friend. “At present, have you been writing anything that you’re particularly enjoying?”

Sylvia sighs. She enjoys the process of writing, but when it comes to prose, the task seems to be much more difficult. She had written hundreds of poems, but prose never came to her as easily. “For me, poetry is an evasion from the real job of writing prose” she admits to her friend.

“Well,” Virginia replies, “we cannot command all our faculties and keep our reason and our judgment nor memory at attention while chapter swings on top of chapter. Writing prose is a kind of lifestyle, I think.” Sylvia nods in agreement, feeling a sense of ease wash over her, for she knows she is not alone in this struggle. “Especially,” Virginia continues, “in a state of illness, which I am sure you empathize with.” Sylvia's head bobs quickly up and down.

“Nevertheless,” Virginia adds, humbly, “still it would be easier to write prose and fiction there than to write poetry or a play. Less concentration is required.” Virginia senses her friend’s mind traveling to some near yet distant past she has had no presence in, no influence on.

The latter sits with Virginia’s take for a moment. Then she replies, “Sure, yes–less concentration, perhaps. But I always was interested in prose. As a teenager, I published short stories. And I always wanted to write the long short story, I wanted to write a novel. Now that I have attained, shall I say, a respectable age, and have had experiences, I feel much more interested in prose, in the novel.”

Virginia smiles. She knows precisely how she wants to respond, but she waits, allowing her friend to continue her curious thought.

Sylvia adjusts her position, unfolding her hands so they both lay open on her thighs. “I feel that in a novel, for example, you can get in toothbrushes and all the paraphernalia that one finds in daily life, and I find this more difficult in poetry. Does that make sense?”

“Definitely it does,” Virginia assures her. “In different words, the poet gives us his essence, but prose takes the mold of the body and mind. It’s a different kind of art, with a different purpose.”

“Exactly.”

They sit, for a moment, in silent unison. Both pairs of eyes stray out the bay window. Virginia catches sight of the death-woven violets resting peacefully below green boughs and flowering branches.

Sylvia is drawn to lines of sundry roses that color the bright green lawn. She feels a sense of gratitude fold over her mind as she ponders the bulging bulbs below. “A little thing,” she thinks, “like children putting flowers in my hair, can fill up the widening cracks in my self-assurance like soothing lanolin.”

“That reminds me,” Sylvia says to her friend, “of one year when I worked for this magazine. At the end of the summer internship, the directors had all the girls in the program pose for photographs. They asked each of us to hold some sort of object that encapsulated our individual ‘essence,’ based on what we wanted to do for a career. When they asked me what I wanted to be I said I didn’t know. I want to be everything.

“They said I had to choose something, so I said a poet. But I mean, how do you represent a poet with a single object?”

“I couldn’t tell you,” Virginia laughs. “The whole world?”

“Well, I ended up with a single, long-stemmed paper rose.”

“Hmm,” Virginia ponders. “Well, I’ve always thought that until we can comprehend the beguiling beauty of a single flower, we are woefully unable to grasp the meaning and potential of life itself. And since that is, in a way, the poet’s desire…”

Sylvia considers. “I guess you are right.” Pausing for a moment, then she continues, “Later, after the photoshoot, I took the rose back home and fitted it neatly under a glass case that was gifted to my mother, by her mother, many years ago, before I was born. For years the jar had been sitting in our living room–untouched, useless.

“I thought, after placing the rose upright within the transparent enclosure, how this inanimate object was precisely what everyone was expecting me to be: a fragile paper rose, never growing, never dying, standing tall and glamorous for all the visitors of our home to see. It was odd too, given that growing up, our home was like a plant nursery: its steamy windows, round tables facing rough glass windows bordered by green potted plants. I guess we stopped buying and growing them after my father died.”

As Sylvia recounts her anecdote, Virginia smiles with care and understanding, for she too has been faced with death from a young age.

She allows the former’s words to sink in before she replies, thoughtfully, “Ah, but how frightening it might have been (and may still be!) to those visitors, and even to one’s own self, when a petal drops from the rose in the jar…”

“Yes!” Sylvia exclaims. “For little did they know that perched humbly behind that real flower was a phantom flower, seemingly invisible, but there.”

“Yet,” Virginia adds to Sylvia’s words, “the phantom was part of the flower for when a bud broke free, the paler flower in the glass opened a bud too.”

Virginia watches as the glow in her friend’s expression rises to the round surface of her face. It is as if the whites of her eyes have been filled with the sun’s rays, emitting light like a star.

Meanwhile, Sylvia thinks, “To learn and think; to think and live; to live and learn; this always, with new insight, new understanding, and new love. How lucky am I to experience this with my dear friend.” Then, speaking to Virginia, she says, “Most people see such a thing and believe it to be nothing more than a dream–and a nightmarish one at that. But how to exactly decipher between a dream and a nightmare? And then what about reality?”

“Absolutely,” Virginia replies. “Behind the cotton wool of ‘reality,’ is hidden a pattern; that we–I mean all human beings–are connected with. Some people just don’t sense it.”

The other nods in agreement. Again she is reminded of a distant memory, something her mother once said to her as they were driving home from the hospital. Keeping her eyes on the road, she muttered, almost under her breath, “Sylvia, let us act as if all this were a bad dream.”

Looking to Virginia, Sylvia says, “To the person in the bell jar–real or phantom–the world itself is the bad dream.”

“Suppose the looking glass smashes, the image disappears, and the romantic figure with the green of forest depths all about it is there no longer, but only that shell of a person which is seen by other people - what an airless, shallow, bald, prominent world it becomes! Yet how glorious when we break free from the borders of that glass house,” Virginia smiles.

Sylvia nods and smiles also. She remembers being trapped inside those hedges, questioning every facet of her existence, the purpose of her living, constantly revisiting the impression that “everything people did seemed so silly, because they only died in the end.” The thought, though it still holds a level of truth, seems largely unimportant at the present moment.

As if the other can sense her friend’s brooding, Virginia becomes evocatively aware of the overwhelming presence of Time. “Time seems endless, ambition vain,” she thinks. “Over all broods a sense of the uselessness of human exertion.” But another voice rings out in her head–one that is louder, more potent.

“There can be no doubt,” she says aloud, “that our mean lives, unsightly as they are, put on splendour and have meaning only under the eyes of love. Wouldn’t you agree?”

“Absolutely,” Sylvia confirms. “And not just romantic love. I mean, I love people. Everybody. I love them, I think, as a stamp collector loves his collection. Every story, every incident, every bit of conversation is raw material for me.”

“Then we are both stamp collectors, with a great deal of beloved stamps.” The women share light laughter. “Stamps of all shapes and sizes, I might add.”

“From every corner of the world,” Sylvia continues. “And how I love them all. I would like to be everyone, a cripple, a dying man, a whore.” She pauses, witnessing, as if from an exterior perspective, the montage of images that have sequenced sporadically in her head. “I guess, perhaps, this is one of the many gifts of being a writer. To occupy another’s black patent leather shoes for an afternoon, a day, a week–and then come back to write about my thoughts, my emotions, as that person.”

“Indeed. The writer is one of many lives, many faces; yet somehow also faceless. We are not as simple as our friends would have us to meet their needs.” Virginia pauses for a moment. “Yet love is simple.”

“Ah, yes,” Sylvia replies. “And if I have learned nothing else, it is to listen and to love: everyone.” She gestures to her friend. “I love you because you are me, in a way–my writing, my desire to be many lives.”

“And mine also,” Virginia replies, kindly. “I have lived a thousand lives already, it seems. But in this life, it is here that we are drawn into this communion by some deep, some common emotion. Shall we call it, conveniently, ‘love’?”

“I don’t know. I think the word is often overused, misused. Love–the four-letter word with far more meanings than we can even begin to understand. But I think we glimpse it authentically here and there, or feel it melting over us in certain moments that seem…extraordinary.”

“This being one of them,” Virginia notes, smiling.

Sylvia smiles also. They sit in silence for a moment, content in one another’s presence. Then Sylvia sighs. “How we need another soul to cling to.”

“We do not know our own souls, let alone the souls of others,” Virginia notes. “But I think it is in the process of connecting with another that we not only come to know them better, but ourselves.”

Sylvia nods. “Human connection is as essential to life as the air we breathe, I believe. So many people are shut up tight inside themselves like boxes, yet they would open up, unfolding quite wonderfully, if only you were interested in them.” She pauses before adding, “I am glad I have found someone with whom I can unfold the great corollas of my Self.”

“And I also,” Virginia replies warmly. “Some people go to priests; others to poetry; I to my friends, I to my own heart, which beats in unison with yours. I feel it–in this very moment.”

An intimacy is shared between the two women. How it is transmuted is unclear: through eye contact, their particular exchange of words, the shared aroma of tea…who’s to say?

A great deal has been said, been shared, but the most is conveyed in this singular moment: enmeshed in the invisible string that runs between these two sets of eyes, these two fugacious bodies, linking them together indefinitely.

At last Virginia says, “The sun is sinking,”

“Perhaps we should head home,” Sylvia replies.

They nod and stand up. After returning their teacups to the tea tray, they gently close the window and depart.

Out in the open air of the world, it appears the brilliant amorous day was divided as sheerly from the night as land from water. People of all shapes and sizes walk the darkening streets. Of our crepuscular half-lights and lingering twilights they know nothing. And in voices that can only be distinguished by the dead, the poets sing beautifully how roses fade and petals fall.

The two women stride, side by side, down the lamp-lit streets of some city, some neighborhood that is, at this moment, nonexistent. Despite the cold air that has taken hold of such a lovely, radiant day, each woman smiles to herself as that feeling, which cannot be labeled with words, unfurls over her mind and body, steeping itself deeply into her soul.

One woman thinks to herself, “I may never be happy, but tonight I am content.” The other, in the same blip of acute awareness, says to herself, “I have had one moment of enormous peace. This perhaps is happiness.”

Just as both wisps of thought begin to fade, mixing into the ever-growing, ethereal black sky, Virginia and Sylvia find themselves each arriving at their destination.

Inside, one observes the yellow-wallpapered room glowing subtly in the unraveling twilight; and from the outside, the window slowly slowly coming alive in a chiaroscuro of shadows and stars. Below the enormous bay window, an elm tree with freshly greening leaves dances in the wind. Next to it, a weeping pagoda kneels humbly toward the ground. The trees are separated by two gravestones, beneath which their roots intertwine.

There I stand, and if I listen closely I can hear a quiet refrain echoing in the breeze:

all the lives we ever lived and all the lives to be

are full of trees and changing leaves.

I am Home.

e e cummings, landscape in blue, Oil On Canvas, 12" x 10", not dated.

Works Cited

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Virago Press, 1981.

Orr, Peter. Interview with Sylvia Plath, The Spoken Word, 1962, https://youtu.be/fAss2OpuUiE?si=qwsDV-scOqbnXLdj.

Plath, Sylvia. “Ariel,” Ariel, Faber & Faber, 1965.

Plath, Sylvia. “The Beekeeper’s Daughter,” The Colossus and Other Poems, Vintage International Ed., 1998.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar, Faber & Faber, 2005.

Plath, Sylvia. “Initiation,” Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, Faber and Faber, 1977.

Plath, Sylvia. The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, First Anchor Books, 2000.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own, Penguin Books, 2004.

Woolf, Virginia. “A Sketch of the Past,” Moments of Being. Ed. Jeanne Schulkind. 2nd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1985, pp. 72.

Woolf, Virginia. “On Being Ill,” London: Hogarth Press, 1930.

Woolf, Virginia. The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays, London: Hogarth Press, 1950.

Woolf, Virginia. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 3: 1925–1930. Ed. Anne Olivier Bell. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980, pp. 36.

Woolf, Virginia. “The Journal of Mistress Joan Martyn,” 1906.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves, Mariner Books Classics, 1950.

Written by Brinn Wallin for UCLA class, “Virginia Woolf,” Professor Louise Hornby, Final Creative Project

This short story was created and written by Brinn Wallin. Please do not steal or copy without permission.

*All Rights Reserved*